In the aftermath of a tragic accident that made a mess of his marriage, Malcolm Mays retreats to rural Oregon in an attempt to begin again, however he gets more than he bargained for when he moves into a foreclosed home in Ione.

In a sense he inherits its former occupant, a convicted criminal called Dusha Chuchonnyhoof, who—having been unjustly jailed for two lifetimes and a day, he says—is preparing to reclaim his property. “The homeowner is only absent, you must understand. Not gone. The end of the sentence approaches […] and when it comes, I will return.”

This much Malcolm is made aware of—this much and no more, for the moment—through the letters that mysteriously appear in and around the house. Letters sent, evidently, from the nearby penitentiary, bidding him welcome… but how can that be when he hasn’t announced his presence to anyone? Other letters are delivered later: missives urging our man to prepare the place for Chuchonnyhoof’s homecoming… despite the fact that the felon in question has been dead for half a century.

Malcolm has no intention of doing what the letters advise, but, as if sensing his resistance, Chuchonnyhoof—or else the degenerate purporting to be Chuchonnyhoof—promises to make it worth his while. How? By bringing his lost boy back from the beyond. “If you do as I tell you to do, he will return when I do. If you do not,” warns one of the murderer’s many messages, “he will remain where you left him.”

Miserable as he is, and much as he would love to hold Row once more, Malcolm still isn’t willing to accept that what’s happening to him is supernatural in nature. Instead, he swallows the local lore whole:

It was easier to think there was some hidden clause in the papers I’d signed, something that said I needed to pay for a murderer’s burial, than to think that the pages and pages of letters littering my hallway were written by that same iron-skinned murderer. Better to think that, even if it meant realising that my grip on sanity was less than I’d thought after Row’s death.

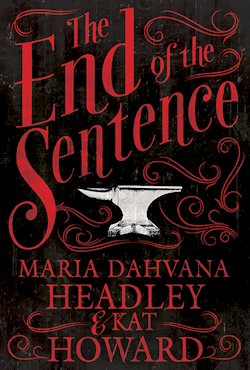

So: is Malcolm losing his mind, or being haunted by some ancient evil? The End of the Sentence leaves little room for ambiguity in the answer its authors offer. I rather wish it had—the presence of plausible alternatives lends crucial credence to the ghostly goings-on texts of this type tend to document—though I don’t doubt its definitiveness will please some readers.

In every other respect, however, this novella-length collaboration between Queen of Kings’ Maria Dahvana Headley and World Fantasy Award-nominated author Kat Howard is a wonderful piece of work: a cleverly conceived and confidently crafted explication of the ways in which yesterday’s mistakes are at most a memory away.

A certain tension is felt, in fact, from the first. Initially, it takes the shape of “something quieter than anger, anticipation rather than rage,” but of course this sense of suspense grows as the story goes. Eventually, it manifests as menace when “the world of the quick had pressed itself hand to hand with that of the dead” in a last act as surreal as The End of the Sentence’s beginning is sinister.

The mystery, in the interim, is gripping; the setting suggestive and nicely isolated; the recurring characters relatively credible, and more complex by the end than expected. Malcolm himself is never less than sympathetic, and deftly developed—not least by dint of the dreadful events that led to his son’s death, which Headley and Howard dole out in digestible portions over the course of the whole.

The End of the Sentence only really represents an evening’s reading, but be prepared to feel the fallout of this fairytale—perfectly formed from a hodgepodge of half-forgotten mythologies—for far longer than the few hours it takes to unfold.

The End of the Sentence is available now from Subterranean Press.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He’s been known to tweet, twoo.